Researchers in Indonesia have created a new device that could help control stray cat populations — and make it easier to return lost cats to their owners. The team, led by Muhammad Irham Bagus Santoso of IPB University, developed an intravaginal device (IVD) that works as both a cat contraceptive and identity device. Their findings were published in the peer-reviewed Open Veterinary Journal.

An intravaginal device for cats

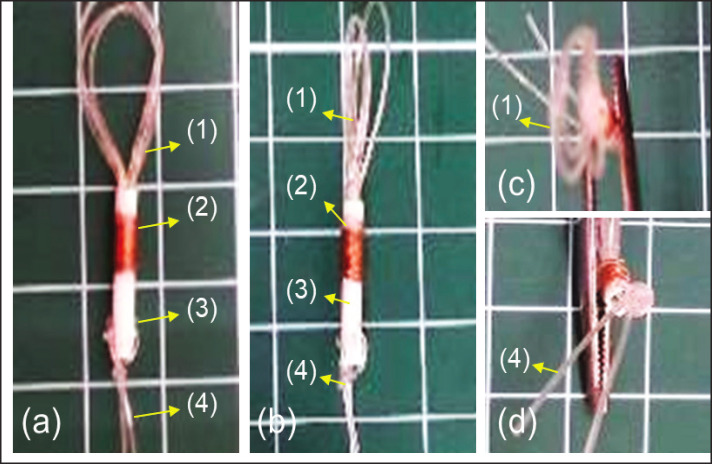

The IVD is made of a small plastic tube and copper wire. It’s inserted in the vaginal lumen, the tube-like central space within the vagina, and held in place by a nylon retainer. It prevents pregnancy by releasing copper ions, which impair and disrupt the motility (movement) of sperm deposited in the vaginal lumen.

A radio frequency identification (RFID) chip inside the plastic tube can be read with a hand-held scanner, similar to microchips implanted under the skin. The chip contains a unique identification number that can link to the cat’s medical records or contact information for the cat’s owner.

Copper intrauterine devices (IUDs, used by humans) prevent pregnancy in a similar way. However, adapting them for cats has been difficult due to the anatomical structure of the feline cervix (the canal between the vagina and the uterus), which is tight with a narrow lumen. Positioning a contraceptive device in the vaginal lumen instead is a promising alternative.

Fabrication of the intravaginal device (IVD) used in research cats. (a) Parts of the IVD, (b) Side view, (c) Bottom view, and (d) Top view. Note: 1 = These oval-shaped nylon strands serve as the primary retainer to secure the IVD within the vaginal lumen, 2 = Copper wire winding, 3 = RFID Chip, and 4 = This nylon “marker” serves as a visual indicator at the vulva and as a removal mechanism – someone can pull it to withdraw the IVD. Images used under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License.

A nonsurgical alternative to spay

Spaying is the most common form of contraception for female cats, but it’s relatively expensive, invasive, and not always available — especially in low-resource areas. This non-surgical cat contraception and identity device offers a promising alternative.

It’s also removable and reusable, making it a more flexible option than surgery. Because it includes a scannable ID, it could reduce the number of cats that end up stray or in shelters.

What’s next?

This study established that the IVD is biocompatible, meaning it can function safely and without causing adverse effects or reactions in cats.

However, the study had shortcomings and limitations. It only included five cats, and had a short, one-week duration. Additionally, on the day after scientists inserted the IVDs, four of the cats expelled them because the nylon retainer did not hold them in place.

The authors note that future research should include a larger sample size, a longer monitoring period, device design improvements, and a mating trial.

If a future version of this IVD proves effective, it could become part of a broader strategy to control stray cat populations.

A second nonsurgical option: the vaginal plug

Several members of the same research team, led by Sella Sofia Ainun, are also developing a vaginal plug contraceptive for cats. This device is small, soft, and degradable. Researchers made the plug from chitosan and PEG 4000, materials commonly used in medicine and drug delivery. Chitosan comes from shellfish shells and supports wound healing. PEG 4000 is a water-soluble, non-toxic polymer often used in pharmaceuticals.

Each plug measures just 10 mm long and 0.3 mm thick. Veterinarians insert it using a simple applicator. The plug sits inside the vagina, where it may block sperm from reaching the uterus. It does not rely on hormones or surgery.

In this early study, scientists focused on biocompatibility, not effectiveness. They wanted to make sure the plug was safe for cats. The cats showed no serious reactions. Their bloodwork and vaginal health remained normal after the device was inserted.

This work is still in the early stages. Researchers will need more studies to test how well the plug prevents pregnancy. Still, it’s encouraging to see multiple non-surgical cat contraceptives in development. These tools could make cat population control more humane and accessible.

Why new cat contraception matters

The world has about 700 million domestic cats. They live on every continent except Antarctica. They’ve spread far beyond their native range—even to remote islands. Nearly 380 million are feral or homeless, according to international estimates. Feral cats face disease, injury, starvation, traffic, and abuse.

Feral cats also pose a serious threat to biodiversity. One study says feral cats caused at least 14% of global extinctions in birds, mammals, and reptiles. They now threaten almost 8% of the world’s most endangered species. They appear on global lists of top invasive threats. In places without natural predators, native species can’t compete.

Some communities use Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) to manage cat populations. But TNR is resource-intensive, and experts say it only works if at least 88% of cats in a colony are sterilized. That’s a high bar for most programs. A simple, reversible, and affordable contraception device could be a game-changer. It could ease pressure on wildlife, protect endangered species, and improve life for the cats themselves.

See our other news articles on pet health topics.