Hundreds of millions of people receive influenza vaccines each year. They clearly provide specific protection against the flu — reducing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths. But we don’t understand their “nonspecific effects” as well. What are their other benefits — or harms? A recent scientific study sought answers. The takeaway: flu vaccination is a “net positive”!

What are nonspecific effects?

Most of us think of vaccines as targeted shields. A flu vaccine, for example, is designed to help our bodies recognize and fight the influenza virus. We call these “specific effects” — protection against a particular disease caused by a specific microbe.

But vaccines can also influence how our immune system responds to other infections. We call these broader influences “nonspecific effects.” Some of them are beneficial, helping our immune defenses become more alert. Scientists have long observed such effects in vaccines like measles, BCG (for tuberculosis), and the oral polio vaccine. Other vaccines might have unintended downsides.

Vaccines do more than just create antibodies against one germ. They also train parts of the immune system that don’t rely on antibodies — such as innate immune cells that act as first responders to infection. This kind of “training” can make the immune system respond more quickly or powerfully to other microbes. That’s a positive nonspecific effect.

However, the same changes might sometimes make the body overreact or become temporarily less effective against certain pathogens. That’s a negative nonspecific effect. Understanding these broader effects helps researchers design safer and more effective vaccines.

Influenza vaccines also have nonspecific effects. What might they mean for human health?

Lessons from other vaccines

The idea of nonspecific effects first gained attention from studies in children. The BCG vaccine, for example, appears to protect not only against tuberculosis but also against some respiratory infections and even sepsis.

A 2023 meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that BCG vaccination reduced the risk of non-tuberculosis respiratory infections by about 44%. Other research found that early BCG vaccination was linked to lower hospital mortality from sepsis.

The measles vaccine has been linked to lower death rates from diseases unrelated to measles.

We’re also starting to understand how vaccines supercharge the immune system to fight other diseases. Studies have found that BCG vaccination can stimulate the production of certain white blood cells and neutrophils that improve resistance to blood infections.

On the other hand, some studies found that the diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) vaccine might increase susceptibility to other infections in certain contexts. In West Africa, children who received DTP as their most recent vaccine were more likely to die from unrelated infections.

A growing body of research suggests that live vaccines, such as BCG, measles, and oral polio, tend to produce beneficial nonspecific effects. They appear to “train” the immune system to respond more effectively to a wide range of microbes. In contrast, non-live (killed or inactivated) vaccines, like DTP, are more likely to have negative nonspecific effects, such as increasing vulnerability to other diseases or raising overall mortality risk in some settings.

Timing also matters. Evidence indicates that the most recent vaccine given has the strongest nonspecific effects. Therefore, when children receive multiple vaccines, experts suggest it may be best to administer a live vaccine after a non-live one to maximize benefits and reduce potential risks.

These findings suggest that the body’s immune response to one vaccine can ripple outward, shaping how it reacts to many other microbes. See our project page on the non-specific effects of vaccines.

What we know about flu vaccines

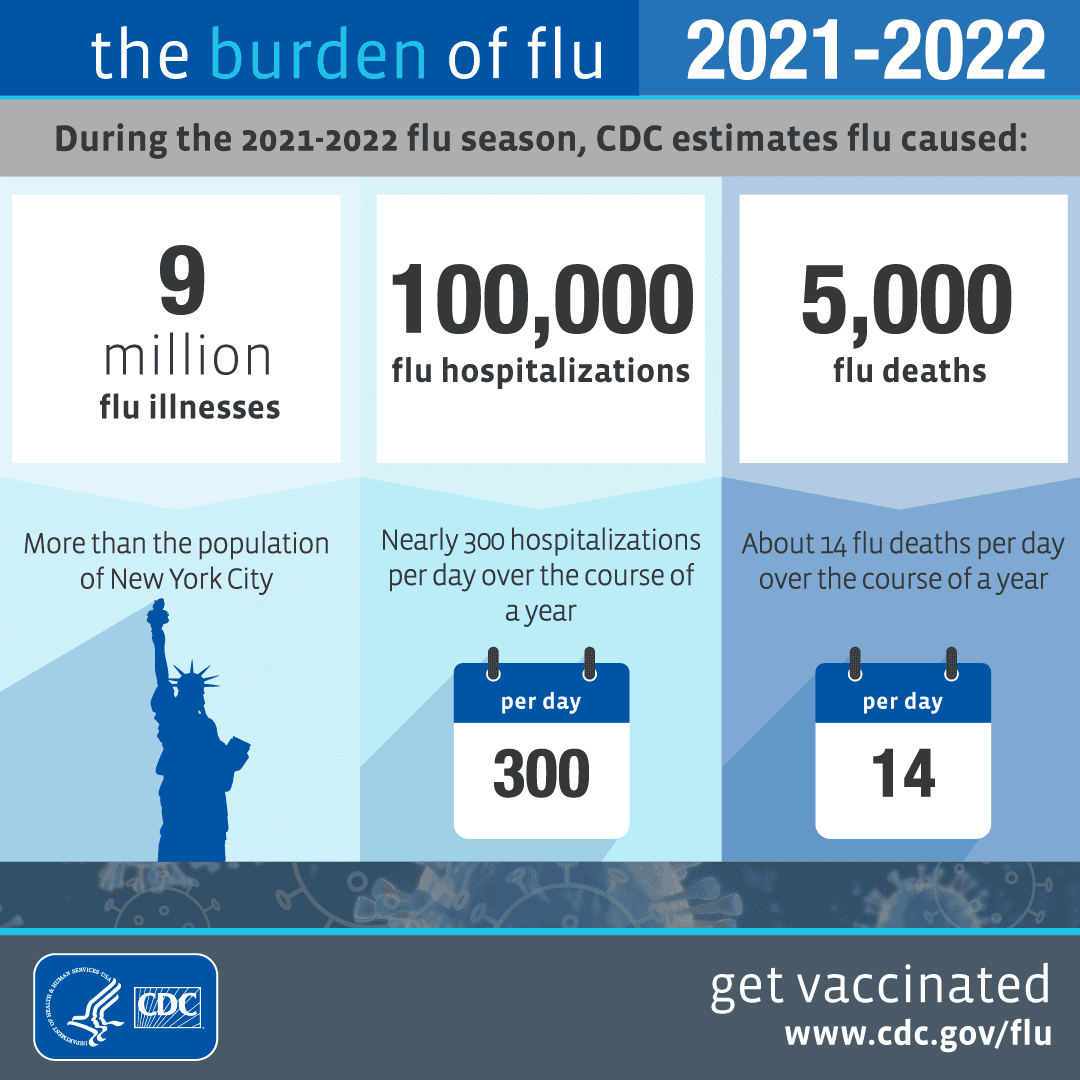

More adults receive influenza vaccines than any other vaccine. The high incidence of seasonal flu and the need for regular, annual vaccination drives sustained demand for influenza vaccines. However, some health authorities are hesitant about how widely to recommend influenza immunization due to competing health priorities and other factors.

Furthermore, many people hesitate to get a flu shot due to concerns about side effects, misconceptions about vaccine effectiveness, and a lack of perceived risk from the flu itself — even though seasonal influenza annually causes an estimated 290,000 to 650,000 respiratory deaths worldwide.

To provide more clarity on the effects of influenza vaccines, two Italian scientists, Nicola Principi and Susanna Esposito, conducted a narrative review and published the results in Vaccines.

A narrative review is a type of scientific publication that summarizes and synthesizes existing literature on a topic.

Their review found that some studies hint that flu vaccines might boost resistance to other viral infections, possibly through a mechanism called trained immunity, where innate immune cells “remember” prior encounters and react more vigorously the next time. For instance, some data suggest lower risks of severe bacterial infections or other respiratory illnesses among flu-vaccinated individuals.

However, the evidence isn’t consistent. Other research shows no such benefit — and a few studies even hint at possible negative nonspecific effects, such as a temporary rise in susceptibility to unrelated respiratory viruses right after vaccination. These mixed findings make it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

Why it’s complicated

Several factors may influence these nonspecific effects. The type of flu vaccine matters — live attenuated vaccines may stimulate the immune system differently than inactivated or mRNA vaccines. Timing and frequency of vaccination can also play a role. Moreover, age, prior infection history, and underlying health may change how people’s immune systems respond.

Because of these variables, scientists are cautious. The same vaccine might have positive nonspecific effects in one population and neutral or negative ones in another.

A key benefit: controlling antimicrobial resistance

According to the review, research suggests that getting the flu vaccine may help slow the rise of antimicrobial resistance. This growing global health threat makes bacterial infections harder to treat. Misuse and overuse of antibiotics are the main drivers of antimicrobial resistance, which has already led to more severe illnesses, longer recoveries, and higher death rates.

Studies show that flu vaccination can reduce the need for antibiotics by preventing flu-related bacterial infections, thereby helping to limit the spread of resistant bacteria. If confirmed, this link could make influenza immunization an important tool not only for preventing flu but also for fighting antibiotic resistance.

Future research can provide more answers

Researchers agree that influenza vaccines are essential for preventing flu and saving lives. But they also see an opportunity to learn more about their broader immune effects. Future studies could clarify how flu vaccines influence overall infection rates, inflammation, and even the body’s response to unrelated pathogens.

Better understanding these nonspecific effects might help scientists design vaccines that not only prevent a single disease but also strengthen general immune resilience — especially in children, older adults, and people with weaker immune systems.

In short: Flu vaccines protect us against influenza, but they may also shape how our immune systems react to other infections. These nonspecific effects — both good and bad — remain an active area of research. Unlocking their secrets could make future vaccines even more powerful.

The Parsemus Foundation supports research on the non-specific effects of vaccines to improve human health. See our project page on the topic. See our other news articles on vaccines.